In 2024, millions of people continued to be affected by disease outbreaks, exclusion from healthcare, and crises such as wars, conflicts, and natural hazards in more than 75 countries. Around 69,500 Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) staff provided assistance where and how they could.

Conflicts in the Middle East

Following the attacks by Hamas on 7 October 2023, the Israeli forces’ war on people in Gaza continued to have a devastating impact on the lives of Palestinians. The war stoked tensions and insecurity across large parts of the Middle East, also escalating conflict in Lebanon and Yemen.

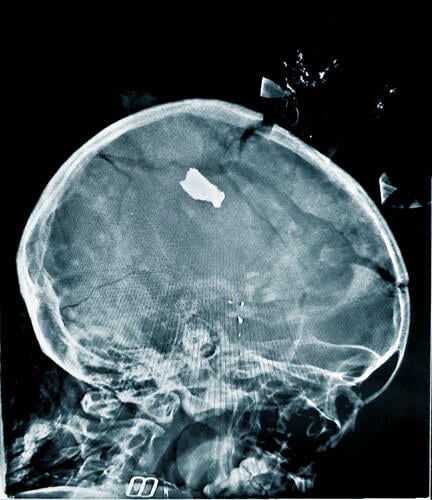

Israeli forces unleashed a relentless campaign of airstrikes and ground incursions, starting from the north of the Gaza Strip, and moving down towards the southern border, obliterating entire neighbourhoods. Our teams treated thousands of patients for war wounds, diarrhoea and skin diseases, as well as psychological trauma, in addition to treating pregnant women and children. However, our efforts to scale up activities were hampered by the Israeli forces, who placed the Strip under a siege, and imposed cumbersome administrative and logistics controls on supplies entering Gaza. As a result, trucks carrying essential medical supplies were routinely blocked. Meanwhile, insecurity forced us to stop activities, evacuate, and then restart, having to adapt to the constantly changing situation. At the time of writing, 11 MSF colleagues have been killed since the start of the war; we miss them, and we mourn their loss.

Communities across the West Bank in Palestine also suffered the fallout of the Gaza war. Israeli forces inflicted shocking levels of violence on refugee camps and communities, destroying houses and killing and maiming people during incursions, some of which lasted for days. During these periods, Israeli forces imposed severe restrictions on people’s movements, meaning they could not leave their neighbourhood even to seek – or deliver – healthcare. Despite these inhumane measures, our teams made every effort to reach people in need.

The hostilities that had been simmering between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon since the October 2023 attacks erupted in late September 2024. Israeli forces invaded Lebanon and launched widespread airstrikes, including on the capital, Beirut. Although the campaign was short, it was extremely distressing for staff and patients, who often had to evacuate to escape incursions or bombs. In response, we expanded our activities in areas where we had access, running mobile clinics and donating supplies.

In early December, the Assad regime in Syria fell, following an offensive by opposition forces. At the end of the year, our teams were exploring ways to increase the provision of healthcare in parts of the country that had been inaccessible to MSF for over a decade.

Civil war in Sudan

The conflict in Sudan entered its second year in 2024, with the Sudanese Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces continuing to fight across swaths of the country. Bureaucracy and security constraints thrown up by the warring parties complicated our ability to respond. The limitations imposed meant we were not able to respond on the scale the immense needs of people demanded; the absence of other humanitarian organisations and a lack of aid in many areas meant that some situations of mass displacement, famine, and violence went overlooked or were severely underserved.

In Darfur, a siege imposed on Zamzam displacement camp and the nearby city of El Fasher from May, meant that scarcely any medical supplies or therapeutic food could be delivered. Malnutrition in the camp increased to such a level that famine was declared in August,1 yet the lack of supplies forced us to cease our outpatient malnutrition treatment in October. During the year, insecurity, including the shelling of hospitals, forced us to evacuate El Fasher.

Our teams in Sudan, and in neighbouring Chad and South Sudan, where many Sudanese have fled, treated patients for life-changing trauma injuries caused by explosions, as well as horrific sexual violence and diseases that spread rapidly in conflict and displacement settings, such as cholera, malaria, and hepatitis E.

Forgotten crises

Violence between armed groups and the police further intensified in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, making it one of the most dangerous places anywhere for our teams to operate. The healthcare system has collapsed, and many people are forced to live in informal displacement sites, with little access to clean water and sanitation services. In mid-November, following an attack on an MSF ambulance by police and self-defence groups, in which two patients were executed and accompanying staff members tear-gassed and threatened, we temporarily suspended all activities in Port-au-Prince. By the end of the year, we had started to resume some of these activities.

In Myanmar, the ongoing conflict in Rakhine state continued to cause widespread displacement and suffering, yet drew almost no international attention. Lives and property were deliberately destroyed, and many people forcibly recruited into military service. Despite severe restrictions on our operations and repeated attacks on our facilities, we worked to deliver care, adopting alternative strategies, such as teleconsultations, wherever possible.

From January, there was a surge in fighting between the Congolese army and M23 and other armed groups in North Kivu and South Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with people and medical facilities repeatedly caught in the crossfire. MSF offered medical and humanitarian assistance in several locations, including sites around Goma, North Kivu’s capital, where up to one million displaced people were estimated to have sought refuge by May.

Across the countries of the Sahel – such as Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger – our teams continued to respond to the needs of communities enduring ongoing violence and recurrent malnutrition where possible. But we were faced with increasing restrictions on activities and access, and insecurity from both states and armed groups.

Attacks on healthcare

In 2024, we recorded a significant rise in the number of security incidents affecting MSF staff, facilities and infrastructure compared to recent years. This was indicative of MSF operations in closer proximity to frontlines in armed conflicts, and of the volatile security situation in many of the places where we work, such as Palestine, Haiti, Sudan, and DRC. Some of these events – shootings, explosions, raids on our facilities by armed groups, attacks on our ambulances – led us to suspend some medical activities during the year. The decision to halt our services, even temporarily, is never taken lightly. Ultimately, it is the local communities who lose access to desperately needed healthcare.

However, these events are not limited to MSF alone; it reflects what the people we assist and the whole humanitarian community are experiencing. Today, state and non-state armed groups increasingly and flagrantly violate International Humanitarian Law, which is supposed to protect medical workers and infrastructure, and reduce the space in which humanitarians can safely work.

Sexual violence

Sexual violence is prevalent in many of the places where we work, especially in conflict settings, such as Sudan, where it is used as a weapon of war. In DRC, numbers are particularly high. In 2023, our teams treated two victims or survivors of sexual violence every hour – a total of over 25,000 people across five provinces during the year. Alarmingly, this trend increased in 2024; in just displacement sites around Goma, North Kivu province, over the first five months, we treated almost 17,500 patients.

Our teams working in the Darién Gap, between Colombia and Panama, and in other locations along the Central American migration route, such as Mexico and Guatemala, treated many women and girls who had been raped or sexually assaulted by criminal gangs in 2024.

People on the move

In December, we were forced to end our Central Mediterranean search and rescue activities with our ship, the Geo Barents, due to a hostile political climate and new migration laws in Italy, which made our operational model untenable. This decision came after the Geo Barents was subjected to multiple 60-day detention orders. Along with the European Union, Italy’s laws and policies reflect a genuine neglect for the lives of people seeking refuge and safety.

Most of the people crossing the Mediterranean embark from Libya, where they have been subjected to extreme violence and abuse. In Libya, MSF treated people for the mental and physical trauma of abduction, trafficking, assault and sexual abuse, as well as illnesses exacerbated by dire living conditions and a lack of healthcare. In this context, we successfully negotiated to evacuate people in Libya we identified as needing urgent treatment to Italy, where they are cared for.

People on the migration route from southern to northern America continue to face physical and mental abuse. In response we worked in Panama, Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, and the United States during the year, where we provided medical and mental health treatment.

In addition to addressing the needs of people displaced by violence across large-scale activities in DRC, South Sudan, or Sudan, we also responded to people in areas such as Mali and Mozambique. In Niafounké, we provided healthcare to people fleeing conflict between non-state armed groups and the Malian army. In Mozambique, ongoing violence in Cabo Delgado province continues to force people to leave their homes.

Responding to medical crises

Since 2022, our teams have responded to a continuous cycle of large cholera outbreaks, including in Yemen, Sudan, South Sudan, and DRC, countries marked by conflict and displacement, which are key drivers of this highly contagious and potentially deadly disease. In 2024 we also launched activities in other places, such as Comoros, where we had never worked before; Zambia, where we returned for the first time since 2018; and Tanzania. Our response to these large and prolonged outbreaks was hindered by the lack of cholera vaccines, due in part to the high demand, and to the fact that one of the two principal oral vaccine manufacturers ceased production.

Throughout the year, MSF teams treated high numbers of malnourished people, mostly children, but increasingly women, especially in Afghanistan and Yemen. Our teams saw disastrous levels of malnutrition in parts of Darfur, Sudan, as well as in Zamfara state, northwest Nigeria, where a mass screening conducted in June revealed that, in two areas, one in four children under the age of five was malnourished. This crisis is aggravated by a global decrease in funding for malnutrition, which has reduced the availability of ready-to-use therapeutic foods, for both preventive and treatment purposes.

In 2024, an outbreak of mpox, a contagious, viral illness that can be fatal if left untreated, began to spread in DRC and subsequently to other countries in Africa, before the World Health Organization declared it a public health emergency of international concern in August. Our teams responded to mpox in DRC, Central African Republic, and Burundi.

Shrinking space for humanitarian aid

After 32 years, we were forced to end our medical activities in Russia in August, when the Russian Ministry of Justice decided to withdraw the registration of the MSF section that ran our activities. This was a blow to the people we were serving in the country, including tuberculosis patients in Arkhangelsk region; people living with HIV in Moscow and St Petersburg; and refugees and internally displaced people affected by the war in Ukraine. We would like to return to Russia, if and when the authorities permit us to.

In recent years, funding for humanitarian aid has been diminishing, as is evident from the increasing gaps in healthcare and the growing needs in the countries where we operate. Sadly, this trend continued in 2024 and into 2025, with many countries cutting or redirecting funds for aid. While we are not directly financially affected by these funding cuts, we are deeply concerned. It is clear no single organisation can fill the enormous hole in the international aid system. Nevertheless, we remain committed to providing independent and impartial medical humanitarian aid to people who need it.

*MSF Directors of Operations: Dr Ahmed Abd-elrahman, Akke Boere, Renzo Fricke, William Hennequin, Dr Sal Ha Issoufou, Kenneth Lavelle, Mari Carmen Viñoles Ramon