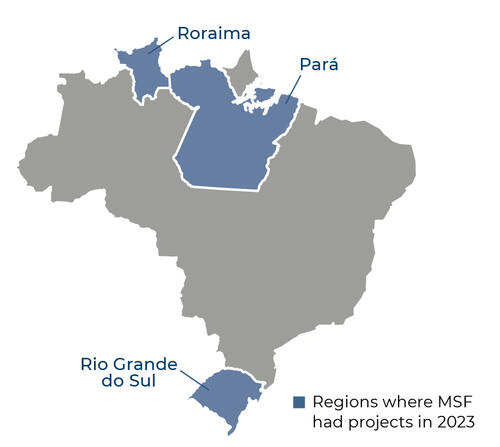

In Roraima state, we work in the Yanomami Indigenous Land (YIL), in the Auaris region, offering general healthcare and treatment for malaria. In the state capital, Boa Vista, we provide medical consultations and mental health support at the health centre for Yanomami people.

The YIL is the country's largest Indigenous territory, and has been under a declared health emergency since 2023. Since then, we have supported the Ministry of Health to respond to the crisis linked, among other reasons, to environmental degradation caused by illegal mining. Not only have traditional fishing areas been damaged, contributing to food insecurity, but the land has been scarred with holes that fill with rainwater, creating ideal breeding conditions for mosquitoes and the spread of malaria.

Meanwhile, in the northern state of Pará, we opened a new project in Portel, an Amazonian town about 16 hours by boat from the state capital, Belém, to assist communities who face difficulties in accessing healthcare. Riverside communities are particularly affected due to their remoteness from health facilities and a lack of professional healthcare workers. Working alongside the municipal health department, we aim to improve access to sexual and reproductive health services, general and mental health care, and support for victims and survivors of sexual violence.

In addition to these activities, we launched an emergency response to assist people affected by flooding in the Taquari valley, in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, in the second half of the year. For around three months, we gave training to local psychologists and health, education and social assistance staff. We also provided hygiene kits and other health promotion activities for people who had to move into shelters.

At the end of the year, we concluded our activities supporting Venezuelan migrants living in Roraima. For five years, we provided medical and mental health services in Boa Vista and Pacaraima, on the Venezuelan border.