Measles is a highly contagious viral disease for which no treatment exists. The only way to fight it is vaccination and treatment of the symptoms in the hope that the patient will be strong enough to naturally fight off the infection.

The measles epidemic declared in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) on 10 June is the deadliest the country has experienced since 2011-2012. Between January and early August 2019, over 145,000 people have been infected and 2,758 have died. Since July the epidemic has worsened, with a rise in new cases reported in several provinces.

Only US$2.5 million has been raised out of the US$8.9 million required for the Health Cluster response plan‘Health Clusters’ are WHO-lead mechanisms to coordinate the health-related activities of UN and non-UN organisations. As is the case in most countries of operation, MSF liaises with the UN’s Health Cluster in DRC but is not a formal member or partner of the Cluster. For more information on Health Clusters: www.who.int/health-cluster/about/cluster-system/en/ – in stark contrast with the Ebola epidemic in the east of the country, which attracts multiple organisations and hundreds of millions of dollars in funding.

While a rapid and adapted response is critical to limiting the impact of measles in communities, on the ground we note the absence of actors and a flagrant lack of much-needed assistanceKarel Janssens, MSF head of mission in DRC

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been fighting the outbreak alongside local Ministry of Health teams through regular projects and emergency interventions reaching a total of 13 provinces around the country.

Since the beginning of the year, MSF has vaccinated 474,860 children between six months and five years old and provided medical care to 27,440 patients.

Most recently, we have been sending teams to new areas such as the province of Mai-Ndombe, in the west of the country, where an emergency team is working to limit the spread of the epidemic in the health zones of Kwamouth, Bolobo and Nioki along the Kasai river. Set up to be mobile and agile, the team moves its base continuously, enabling them to adapt to the needs identified on the ground and reach people in remote areas where access to healthcare remains extremely challenging.

Measles in DRC: 3 questions in 3 minutes

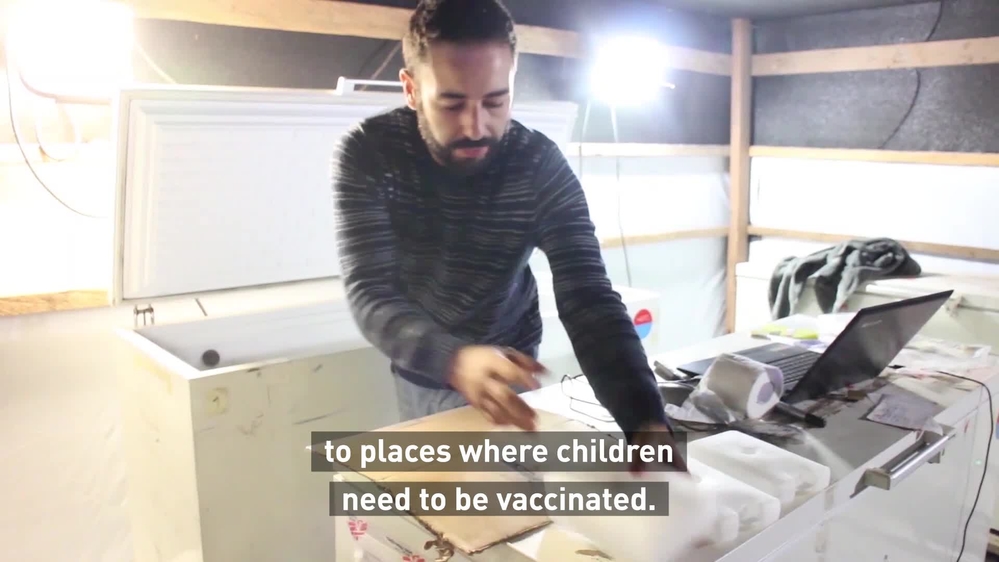

“Just getting vaccines to places where children need them is a huge task. They need to be kept within strict temperature limits, which means setting up a ‘cold chain’. This requires refrigerators, generators, fuel and fast transportation, as well as a maintenance system. Many health zones do not receive any support from other organisations, despite evident needs,” explains Pierre Van Heddegem, field coordinator of MSF’s measles emergency team.

Unless there is a massive mobilisation of funds and response organisations, this outbreak could get even worse.

“Two months after the official declaration and few weeks before the start of the school year, the measles epidemic shows no signs of slowing down. In fact, since July the epidemic has worsened, with a rise in new cases reported in several provinces,” Karel explains.

If we want to contain the outbreak, it is imperative to strengthen the response, and to do it immediatelyKarel Janssens, MSF head of mission in DRC

MSF has been working in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) since 1977. The organisation has several emergency response teams across the country to respond to health and humanitarian emergencies (epidemics, pandemics, population displacement, natural disasters, etc.). These teams ensure epidemiological surveillance and when necessary provide emergency-response medical action aimed at limiting illness and mortality.