Once considered a disease on the decline, the social and economic downfall that followed after the collapse of the Soviet Union has sparked an escalation of the TB epidemic in many post-USSR countries, including Ukraine. The country’s prisons are a hotbed for the disease, with prevalence rates more than ten times higher than in the rest of society. In the Donetsk region in eastern Ukraine, MSF now provides treatment and support to over 140 inmates and ex-inmates suffering from multi-drug-resistant (MDR) TB.

“It’s hard to sit up and I’ve got pain everywhere”, says Andriy*, 31, in a coarse voice, behind a white protective mask. A drunken brawl a few years ago lead to a jail term for violent assault, and also put an abrupt end to his vocational training to become a construction worker. Half a year ago, while still in prison, he was diagnosed by MSF to have MDR-TB. His body is thin and frail, and he says he has abandoned hope of having a family and living a normal life until he is cured.

Over the next two years, Andriy will have to adhere to a strict regimen of six different TB drugs each day, a painful cocktail that often produces side effects like nausea, vomiting, and loss of sight and hearing. “It’s hard to stand it, but if I don’t continue I will just fall apart” he says.

About 9500 people developed MDR-TB in Ukraine in 2011, according to WHO. The number of new MDR-TB infections in the country has been rising steadily due to outdated prescription practices, insufficient supply of drugs of often questionable quality, and lack of access to diagnostic tools. Interruption or non-compliance to treatment are also major contributors to the development of TB drug resistance. As an airborne infectious disease, it can be transmitted directly from one person to another, especially in overcrowded settings. People living with HIV are usually more susceptible to developing the disease due to a lowered immune system.

The Donetsk region – known as the industrial heartland of eastern Ukraine- has been particularly hard-hit by the HIV/TB epidemic, partly due to a high number of injecting drug users. Since June 2012, MSF teams have been working inside three pre-trial detention centres as well as in Colony 3 – an 800-bed prison hospital where prisoners diagnosed with TB are being held. All inmates in Colony 3 are male and are kept in sparsely equipped cells, housing approximately ten people.

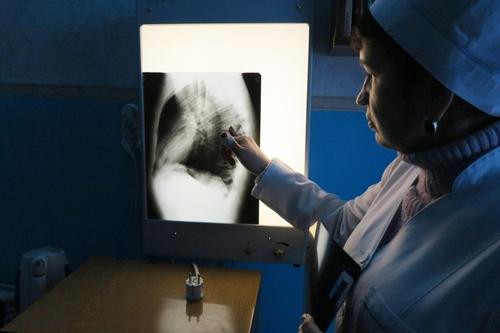

MSF’s support includes diagnosis and testing, provision of medical treatment, and psychological support to help MDR-TB patients continue taking their medication. MSF has also rehabilitated lab facilities and introduced infection control measures to prevent transmission of the disease within the prison walls. In addition, MSF provides antiretroviral (ARV) treatment to patients that are co-infected with HIV.

Inside the prisons, overcrowding, poor ventilation, and frequent prison transfers exacerbate the spread of the disease. Weak nutrition from poor diets also make prisoners more susceptible to falling ill. Almost half of the patients hospitalised in Colony 3 are suffering from drug resistant forms of the disease.

Many prisoners come from difficult socio-economic backgrounds where the burden of disease is already high. “Prisoners are a particularly vulnerable group” says Yulduz Seitniyazova , MSF’s Head of Mission in Ukraine. “They are all living a hard life. Some have a history of drug abuse and alcoholism. They face so many problems, and many don’t believe that taking medication should be a number one priority.”

Before an individual is initiated on treatment, the MSF team strives to ensure that he is committed to stick to the long and painful treatment course. “He needs to know what treatment involves from the very start, and if things get tough we try and motivate him to continue” says Yulduz.

At an international level, MSF campaigns for the research and development of better treatment regimens that are more effective, affordable, less painful and do not put the lives of patients on hold for two years, as in the case of Andriy.

Once patients are released from prison, MSF collaborates with the Ministry of Health and other organisations to ensure that patients complete their treatment. This includes adequate follow-up such as medical, psychosocial and adherence support and monitoring of side effects. Patients who default from treatment are traced in order to ensure that they continue. So far, MSF’s project has had 18 patients on treatment being released from prison – of which 16 are still adhering to the treatment regimen.

“Some have no homes to return to. Some run a great risk of falling into alcohol and substance abuse, which will reduce the chances of adhering to treatment” says Yulduz. “It’s important that these patients also get the necessary support once they’re outside the prison walls to enable them to continue treatment until they’re cured”.

* Andriy is not the patient’s real name.