By the time the current conflict in Sudan broke out in mid-April, its Darfur region had already been facing war and ethnic violence for over two decades. Today’s fighting has rekindled fault lines in communities throughout Darfur, particularly the city of El Geneina.

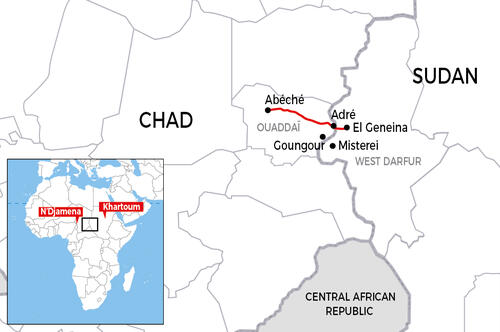

Intense fighting, intercommunal violence, and large-scale attacks against civilians have driven hundreds of thousands of people to flee across the border to Adré, eastern Chad. Like other towns along the Chad-Sudan border, Adré has been struggling to accommodate the rapid, massive influx of refugees as access to food, medical care, and other necessities was already limited before their arrival.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams have been providing care in Adré since 2021, but our operations have scaled up significantly over the past three months to expand capacity in local healthcare facilities and improve the quality of care as large numbers of people continue to arrive from Sudan – often with gunshot wounds and other injuries sustained along the way from El Geneina.

In testimonies gathered in recent weeks, many patients said they were victims of Arab militias inside El Geneina and during their journey to Chad. They report being targeted because of their Masalit identity.

Masses of wounded reach Adré

At the end of May and beginning of June, the violence intensified in West Darfur. Yet only a few wounded people managed to escape across the border to an emergency surgical unit set up by our teams in partnership with the Chadian Ministry of Health in Adré hospital.

On 2 June, a total of 72 wounded patients were treated at the hospital. Most had gunshot wounds and came from the town of Masterei and its surroundings, south of El-Geneina. Upon reaching the Chadian town of Goungour, they received care from Ministry of Health and our medical staff and were referred to hospital.

At the time, there were reports of hundreds – if not thousands – of injured people unable to access vital medical care in Darfur, with many medical facilities looted, damaged, and lacking staff and supplies. The main road linking Adré to El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, was closed at the time.

Everything changed on 15 June, when people managed to escape to Adré after being stranded for two months in El Geneina. Adré hospital received 261 war-wounded patients on that day alone.

Over 800 war-wounded patients arrive in three days

This influx of casualties at Adré hospital was one of the largest, in terms of volume, that our teams have ever seen, with 858 war-wounded people received from 15 - 17 June – including 387 on 16 June alone. Over the following days, the emergency room received an average of 46 wounded patients each day.

The vast majority of patients were suffering multiple gunshot wounds, particularly to the abdomen, back, and legs. They were mainly men, with a smaller proportion of women and children. The youngest patient hospitalised was two months old; the oldest was over 70. Seven patients had already died upon arrival.

Between 15 - 18 June, 62 pregnant women received care for gunshot wounds and injuries from beatings and other assaults.

“The first patient I was called in to see was a woman who had been shot in the stomach and chest while she was six months pregnant,” says Clémence Chbat, MSF midwife.

“We were very afraid for her because a piece of bullet was lodged in her uterus. Unfortunately, the baby died, but she was able to survive.

“It was striking to see so many pregnant women with injuries to their limbs and abdomens. They came from El Geneina and reported terrible scenes such as having to run under bullets at the risk of losing their children on the way, and being attacked and raped,” says Chbat.

With a few exceptions, the wounded patients at Adré hospital belong to the Masalit ethnic group, a non-Arab Darfuri community who live in both Chad and Sudan.

It was striking to see so many pregnant women with injuries to their limbs and abdomens. They came from El Geneina and reported terrible scenes.Clémence Chbat, MSF midwife

Violent attacks against certain ethnicities

A large number of patients say they were attacked by Arab militias in El Geneina and during their escape to Chad. They report being targeted because of their Masalit ethnicity.

Several testimonies report recurring attacks in neighbourhoods such as Al Madares, Al Jabal, Area 13, and Al Jamarik, as well as the presence of snipers targeting civilians venturing out to fetch water or supplies.

“No one was allowed to go in or out [of their home]. People tried to get clean water from some wadis or springs, but snipers were shooting at them. At the beginning there was resistance from Masalit armed groups, but they could not hold.” — N*, 25 years old.

A variety of factors prompted a large part of the Masalit community of El Geneina to try to flee to Chad in mid-June, after several weeks of clashes and violence: the murder of the governor of West Darfur, Khamis Abakar; escalating threats; and reports of a massacre during an attempt to reach a Sudanese army camp in Ardamatta, an area in the eastern part of the town.

A growing humanitarian crisis

Today, around 200 injured people remain in the hospital in Adré. Some of them will need medical care for a long time in order to recover, particularly physiotherapy.

At the end of June, we set up and started working in our inflatable hospital, which includes a sterilisation and X-ray room and two operating rooms, to improve the available capacity and quality of care.

With the wave of wounded, new refugees from El Geneina also arrived in Adré. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), around 130,000 refugees, mainly women and children, have arrived in the town in recent weeks.

This sudden increase in people arriving has generated major humanitarian needs in all areas: medical care, shelter, food aid, water and sanitation, in a place where accessing these needs is already difficult for the local community.

“We used to have between 35 and 50 children in the paediatric unit at any one time, but we are now treating between 200 and 250 children,” says Dr Japhet Niyonzima, MSF medical team leader.

“Eighty per cent of them suffer from severe acute malnutrition with complications. One of the priorities today must be to expand the paediatric and nutritional services in the health centres and refugee sites to treat children earlier, before their condition worsens.”

The authorities and the UNHCR estimate that there were 260,000 new Sudanese refugees in eastern Chad in mid-July. Transit sites are multiplying, and new camps are being set up, including in Arkoum, where our teams have started providing medical care.

Some 400,000 Sudanese refugees were already in Chad before this current conflict, having fled their country during the past 20 years. A large amount of humanitarian aid will have to be provided over the long run to support people in the most vulnerable circumstances.

*Names changed to protect identity.