The land route between Central America and the United States (US) is one of the most dangerous in the world for migrants. People leave their countries in search of safety and well-being. But what they find on the journey between the dense Darién jungle in southern Panama, the northern triangle of Central America, and northern Mexico, is quite the opposite: a succession of risks, violence and hardships that threaten their lives at every turn.

That is what John, a man from Cameroon who spent three days in the Darién eating nothing but peanuts, tells us. As does Barbara, a woman from Venezuela who had to cross with her six-year-old son into Honduras from Nicaragua, along a dangerous path to avoid border control officials. Enel, who has been living on the streets in Reynosa, northern Mexico, also reaffirms the risks of the treacherous journey.

COVID-19, restrictive policies, and violence

The COVID-19 pandemic served as an excuse for the US to impose Title 42, one of the most regressive immigration rights regulations in living memory. In the past three years, according to official figures, Title 42 has enabled the immediate expulsion of nearly two million asylum seekers to dangerous cities in Mexico, under the false pretext of public health.

I don't understand why they make it so difficult for us. All we are looking for is a better life.Barbara, migrating from Venezuela

This is not the only repressive policy in the region. In southern Mexico, raids and checkpoints by immigration officials are repeated every day, serving as a barrier to those moving north. For months, the Honduran government imposed a fine of more than US$200 for migrants who entered the country without documents in order.

While failing to stop people migrating by violating human rights and limiting access to basic services, these policies have an additional perverse effect: they push people into the hands of powerful criminal networks operating throughout the region. Migration has become a multi-million-dollar business, where kidnapping, robbery, extortion and human trafficking are protected by the impunity guaranteed by the inaction, and even complicity, of some officials.

Meanwhile, the number of people who undertake this journey, despite the dangers, continues to increase. Between January and April of this year, encounters between migrants and authorities at the land border of the southwestern US were 46 per cent higher than in the same period of the previous year.According to International Organization for Migration (IOM). Mexico is the third country, after Germany and the US, with the highest number of asylum seekers.According to UNHCR. In 2021, this figure exceeded 130,000 requests for asylum, according to Mexican authorities.

As a result, migration on the continent has become a permanent humanitarian crisis. In addition to the impact caused by administrative barriers and widespread violence, those travelling through the region face multiple limitations in accessing food, clothing, shelter, health, and education. Under these conditions, the physical and emotional well-being of migrants is severely affected.

Responding to needs in the region

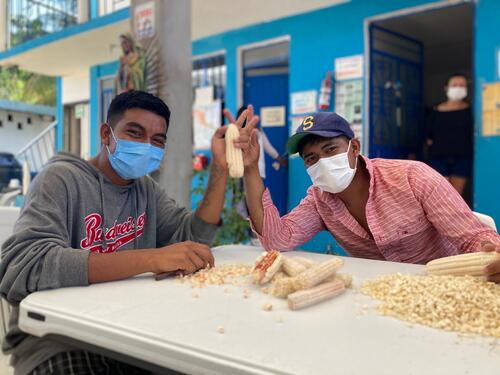

At the San Vicente migration centre in Panama, teams from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provide general healthcare and mental health services to survivors who crossed the Darién jungle, a 5,000 square kilometre swampy area that separates South America from Central America.

One such survivor is John, from Cameroon. Fortunately, the hardships he faced only left him with mosquito bites and body aches, which prompted him to seek medical care. His companions were not so lucky.

“I saw people dying and I couldn't help them,” says John.

Barbara and Enel also received assistance from our teams along the route between Panama and the northern border of Mexico. Between January and June of this year, we provided more than 54,000 general health consultations; 5,500 individual mental health consultations; and 5,000 social work referrals. During this period, more than 23,500 hydration and hygiene kits were also delivered, and nearly 65,000 people were reached through health promotion activities.

“The main physical ailments our teams see during consultations are respiratory, gastrointestinal and skin conditions, which are mainly due to the precarious conditions in which people live,” says Helmer Charris, MSF deputy head of mission in Mexico.

“In addition, people suffer from muscle pains, foot injuries and some even physical trauma due to the long walks they have experienced along the route,” says Charris.

People migrating to the US have diverse backgrounds. While all people are vulnerable, the impact of migration is most profound on children, unaccompanied minors, pregnant women, elderly people, people who identify as LGBTQI, indigenous and non-Spanish-speaking people, extracontinental migrants, and survivors of sexual violence.

“Usually, the violence most people have experienced is at their place of origin,” says Dr Reinaldo Ortuno, MSF medical coordinator in Mexico and Central America. “However, it persists along the route, and generates serious implications on their mental health.”

Usually, the violence most people have experienced is at their place of origin... However, it persists along the route, and generates serious implications on their mental health.Dr Reinaldo Ortuno, MSF medical coordinator in Mexico and Central America

“In addition, the uncertainty of their situation and family separation, among other factors, influence the development of emotional responses such as anxiety, stress, excessive fear, constant worry and, in severe cases, psychological disorders,” says Ortuno.

At the MSF mobile clinic in Danlí, eastern Honduras, Barbara waits for her husband to be treated for the flu, which he picked up over the last days of the trip. Her six-year-old son takes advantage of the space to socialise with other children who are also on their way north.

“We want to get to the US to work and to be able to pay for the lung surgery my little boy needs to improve his health,” says Barbara. “I don't understand why they make it so difficult for us. All we are looking for is a better life.”