Some 71 million people worldwide are infected with the hepatitis C virus. If left untreated, hepatitis C can lead to liver damage, liver cancer and sometimes death.

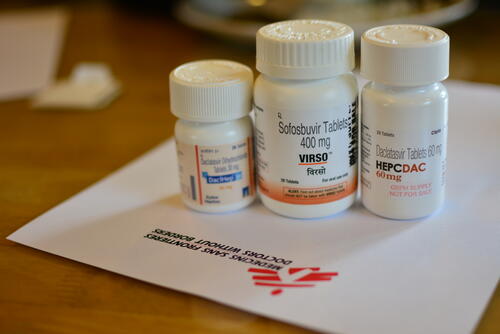

In recent years, effective drugs – known as direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) – have become more affordable. They cure 97 per cent of patients who complete the 12-week treatment course. However, access to diagnostics and treatment with DAAs is still difficult in countries such as Cambodia, where hepatitis C is a major health issue.

Médecins Sans Frontières is working with the Cambodian Ministry of Health to increase people’s access to care at Preah Kossamak hospital in the capital, Phnom Penh, and has introduced innovative ways of diagnosing and treating the disease.

At the start of the project in 2016, it took up to 140 days for patients to start on hepatitis C treatment after being screened. “They were scared,” says MSF’s Dr Sann, who has seen hundreds of patients over the past three years. “They had been told that their blood carried the hepatitis C virus, but they still had to wait a long time before the treatment started. They didn’t know what the virus was doing to their body, and they wondered what might happen to them.”

A simplified model of care for people with hepatitis C

Fewer medical appointments

Vanna Chou started DAA treatment a few weeks ago. “I had symptoms of hepatitis C: a headache, a fever and I felt cold,” he says. “I tried traditional medicine first, but this was not successful. After I saw on Facebook that MSF offers treatment in Phnom Penh, I decided to take the eight-hour bus ride from Siem Reap where I live. At first, I was worried. I didn’t know there was a simple treatment for hepatitis C. But everything was well explained.”

Previously, patients had to visit the clinic eight times for the diagnosis to be completed before treatment could start. However, Chou was able to start his treatment on his second visit to the clinic because of two key simplifications.

First, all patients now receive the same treatment regardless of the type and stage of their liver disease, which means they no longer need most of the pre-treatment analysis required by earlier treatments.

Second, the DAAs are very safe, so additional tests and monitoring, which used to take place before and during treatment, are no longer necessary. In total, patients now have five medical consultations instead of 16, which makes their lives much easier.

Seng Sreymom came to the clinic for her final blood check 12 weeks after completing treatment to discover whether the virus had disappeared completely from her blood. “I am a cleaner and for every appointment I have to ask permission from my boss,” says Seng. “They have to find someone to cover for me. It worked well though.”

The cost of travelling to the clinic is another burden for the patients. “Many people in Cambodia are poor,” says MSF’s Dr Somalene Pa, who has worked in the clinic since 2016. “So it’s a big improvement for patients if they have fewer consultations and have to spend less on transport.”

The way we work here is not limited to Cambodia: the new treatment method can be introduced anywhere in Asia or AfricaDr Sann, working for MSF at Preah Kossamak hospital in Phnom Penh

Treating more patients with the same number of staff

Just as the new treatment is simpler for the patients, it is also more efficient for the clinic’s staff. With the simplified treatment, only one of the medical appointments requires a doctor; the others are managed by nurses. “The responsibilities of the nurses have greatly increased,” says MSF nursing supervisor Savorn Choup. “We triage the patients and many consultations are done by nurses.”

Fewer appointments also mean less congestion in the clinic, and more patients can be started on treatment by the same team. More than 13,000 patients have been treated in the clinic since 2016.

When changes were made to the model of care, the quality of the treatment was observed carefully. The cure rate remains stable at 97 per cent.

Many patients, including Seng Sreymom, agree to receive a phone call a few days after their final blood test to learn the outcome of the treatment, thereby removing the need for another appointment.

We hope to eliminate hepatitis C in Cambodia by 2030Dr Chhit Dimanche, head of the gastrointestinal and hepatology department of Preah Kossamak hospital

Finding infected people before disease breaks out

In the long run, the objective is to further simplify treatment for hepatitis C and bring it closer to the patients, so they no longer need to travel long distances to attend consultations.

To this end, MSF is currently implementing a decentralised model of care, led by nurses and carried out in health centres, in rural districts in Battambang province. If successful, this will multiply the effect of the innovations.

“We hope to eliminate hepatitis C in Cambodia by 2030,” says Dr Chhit Dimanche, head of the gastrointestinal and hepatology department of Preah Kossamak hospital.

“The way we work here is not limited to Cambodia,” adds Dr Sann. “The new treatment method can be introduced anywhere in Asia or Africa. It’s not a mere wish but based on what we have learnt from our pilot project here in the clinic.”