Barrie Rooney, a laboratory scientist from County Leitrim, Ireland swapped her lecturing job in Kent, England to join Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) mobile sleeping sickness team in a remote corner of Democratic Republic of Congo. She describes days getting up before dawn to screen whole villages for the disease and nights spent dodging termites in the rainforest.

I’ve been doing MSF missions for 10 years but I can still be surprised by the sheer determination and resilience of people in remote areas.

Central Africa is covered by huge rainforests with tracts of savannah which the nomadic Fulani herdsmen have used for centuries. The Zande people who survive off the land and the abundance of the forest also live here. The soil is fertile and the climate generous, with no scarcity of water; nutrition is not a problem. This humid environment is also inhabited by the tsetse fly, which carries the parasite causing sleeping sickness.

A non-partisan parasite

Sleeping sickness sounds innocuous, but in fact it is a slow killer. National borders (not recognised by the tsetse fly) criss-cross the forest, bringing rebels, disputes, armies and inevitably refugees. The parasite is non-partisan and will happily migrate with either flies or humans and continue to infect new people and new areas.

I joined the team as it headed off to an area in the northeast of Democratic Republic of Congo. This country is where more than two-thirds of all current sleeping sickness cases are found. Thousands of people live in village communities in the forest, which are so inaccessible that medical care and resources are often absent. Remote, inaccessible and insecure is only the half of it.

Up and screening

Many cases of sleeping sickness were found in this area four years ago but, due to insecurity, it was considered unsafe for medical teams until now. After rehabilitating some old hospital rooms and a convent for lodgings, we hired a new local team. With the arrival of a lorry with supplies after three weeks, we were up and screening.

Diagnosing sleeping sickness is complex, needing trained staff, electrical equipment and a fridge. Jeeps can cope with the main tracks through the forest, but as the rainy season progresses, good bridges become essential for crossing swamps and streams. Where these are lacking, we resort to using motorbikes with eager local chauffeurs. Six technicians and all our equipment – including a generator and microscopes – head off into the bamboo forests to reach the clearings where people live and tend their crops.

Dawn start

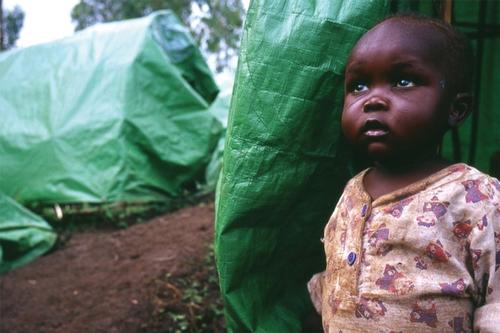

We have to get to villages by 7 am as we need to screen up to 80 per cent of the people living there in order to halt the spread of the parasite. Along the way, people hail us and ask us to screen their sick or disabled relatives in their huts as they are unable to travel to the nearest village. When we find cases, all we can offer is motorbike transport to our rehabilitated hospital, no matter what their age or condition. But without treatment, they would almost certainly die.

Night in the emergency room

As MSF volunteers, we never turn away other medical emergencies, which we treat at an emergency room close to our base. On occasion this can mean working day and night, as happened on a humid full-moon night in May. I was woken at 4 am by a nurse telling me that a two-year-old boy, Jeremy, had arrived with severe malaria and required a blood transfusion immediately. Lab tests are required to ensure that clean, compatible blood is given by the donor. So, accompanied by the guard, we went off down the track to the emergency room, avoiding the snakes. The glowing, misty night also provided perfect conditions for the nuptial flight of the termites, which were attracted to our lights in their millions.

We opened up the lab and started the generator. Jeremy’s uncle was found to be a perfect match. Little Jeremy lay with laboured breathing in his mother’s arms. The search for a vein was long and tortuous for both him and the team. Success at last, as the blood slowly dripped down the catheter into his arm. The guard and I returned to the base through the termite-filled mist to the whooping sound of the locals collecting this bountiful supply of food. As the sun rose at 6 am, the lab team was again ready to leave for another screening day, content that we had done our best.

A bold challenge

It’s been 10 years since my first sleeping sickness project with MSF. In that time I have seen a real decrease in levels of the disease: in 1998 there were 300,000 new cases; today that’s been reduced to 50,000-70,000, which is really encouraging. It may be possible in the near future to completely eliminate this parasite as a threat to the health of millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa. The mobile team I work for are at the centre of this bold challenge.