In Mexico, these people are systematically exposed to further episodes of violence. We have been working with migrants and refugees in Mexico since 2012. Our teams work on Mexico’s southern and northern borders, and at various key locations in between, offering medical, psychological and social support to migrants and refugees along the perilous migration route from South and Central America to the United States.

In Mexico City, we have a comprehensive care centre where we provide specialised multidisciplinary care to migrants, refugees and Mexican people who have been victims of extreme violence and torture. We also provide counselling and mental health services to migrants and refugees outside the Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR).

MSF has repeatedly denounced the repressive policies of the U.S. and Mexican governments based on criminalisation, persecution, detention and deportation in order to contain migratory flows to the northern border. These policies push migrants into the hands of criminal gangs who extort them.

Our activities in 2022 in Mexico

Data and information from the International Activity Report 2022.

215

215

9.4 M€

9.4M

1985

1985

67,700

67,7

8,800

8,8

5,300

5,3

90

9

Reynosa, Mexico: Caring for migrants and deportees

The situation in Reynosa, through the eyes of MSF and the people we assist

MSF has worked in Reynosa since 2017 treating victims of violence in the city, and more recently providing mental and medical care to migrants and deportees

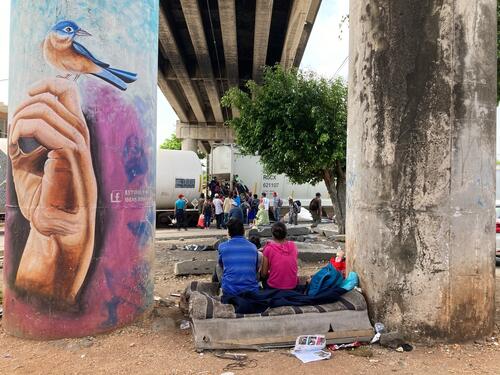

Forced to leave their home countries because of gang violence and poverty, people on the move are increasingly prevented from reaching the US to ask for asylum.

Instead, they find themselves trapped at the border in areas of rampant violence, waiting to cross in deplorable humanitarian conditions.

Our teams have documented a pattern of violent displacement, persecution, sexual violence and forced repatriation. It’s a violence that starts in the country of origin and is replicated along their journeys through Mexico.

"I'm not a criminal"

"I'm not a criminal"

"I fled Honduras because the gangs wanted to recruit me and I refused."

The story of 17-year-old José* is representative of many of the young patients we care for in our projects in Tegucigalpa and Choloma, in Honduras, and Reynosa, Mexico.

- Try a different country, year, format, or topic.

- Clear one or more filters

Contact us

Fernando Montes de Oca 56

Col. Condesa, 06140

Del. Cuauhtémoc, Ciudad de Mexico

Mexico