“It’s between 11am and midday at the moment. Anyone who knows shadows knows that,” says Djeynabou Abdoulaye, smiling. She has come to the village school in Tassakane to get her child vaccinated against measles. “We’re lucky it’s not raining today.”

Despite the official end of the war in 2015, Timbuktu region in northern Mali remains tense, and security incidents and criminality have had a significant impact on people’s ability to access healthcare. This in turn has led to low rates of vaccination coverage, especially among children.

Since February, a number of measles cases have been reported in the area and in September Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), alongside the Ministry of Health, decided to launch a vaccination campaign. The campaign reached over 50,000 children aged between six months and 14 years.

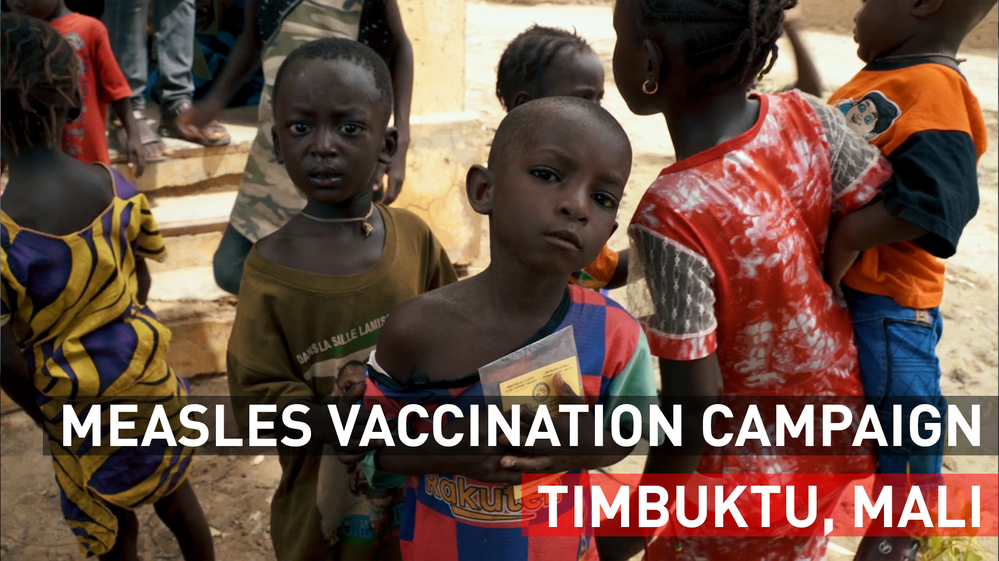

Measles vaccination campaign in Timbuktu

The vaccination was done in three stages in 12 of the 19 zones of Timbuktu, with teams basing themselves in health centres or turning schools or other buildings into vaccination sites for the day. The zones ranged from easy-to-access urban areas to rural ones on the opposite bank of the Niger River, where the backwaters, pools and lakes form a natural barrier.

“It takes an hour to an hour and a half to get there in a dugout canoe,” says Tuo Songoufolo, MSF’s medical adviser for the project. “People tend to spread out over the area to graze livestock or to grow their crops. And that means we need to follow them to be able to vaccinate.”

The campaign also coincided with the beginning of the rainy season, when people move to the river’s edge for fishing and agriculture. The rising water levels mean that the river becomes the only means of access.

This does not deter the mothers though, who are very aware of the spots on the skin and the fever that herald the arrival of the disease. Some travelled from surrounding villages, such as Aïssata Ibrahim, who rented a canoe to make the journey so that her four-year-old daughter could be protected against measles.

The vaccination site in Tassakane is busy. The vaccination team is set up in a classroom, with lessons on a chalkboard in the background. Outside, children and mothers mill around waiting, while others with their yellow vaccination cards are ready to head home.

Mariam Hammadoun Maïga, mother of 16-month-old Amadou explains: “There are people who live far away. And with the water at the moment it’s very difficult for them to come for the vaccination. But despite that they came to get their children vaccinated today.”

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease. The symptoms appear on average 10 days after exposure and include a high fever, rash, runny nose, cough and conjunctivitis. When combined with malnutrition or malaria, the effects of the disease can be devastating. A child with measles can quickly become malnourished or develop other more serious complications that can affect their eyes or their brain.

But there is a safe, cheap and effective vaccine, one of the World Health Organization’s routine childhood vaccinations. The challenge comes in reaching those children who have gone unvaccinated, as well as ensuring that the doses of vaccine are kept at the right temperature, whatever journey they take.

Amadou, sitting on his mother’s lap, watches cautiously as the nurse slips the needle into his arm. He doesn’t cry. “I came because vaccination is vitally important to protect children against disease,” says Mariam. “We say that prevention is better than cure, therefore it’s better to vaccinate children than to treat them.”