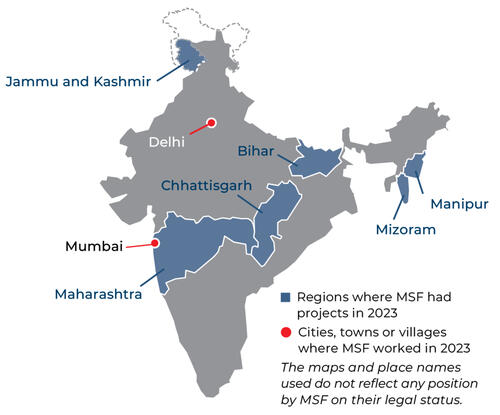

We have a number of long-standing projects in India, which we run in conjunction with the state authorities to address specific healthcare needs and emerging public health concerns.

We also run mobile clinics in remote areas of the country, where even preventable, treatable conditions such as malaria can assume life-threatening proportions.

Key activities

Through our independent clinic and outpatient department (OPD) managed in collaboration with Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) and National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP) we provide medical and psychosocial care to people living with drug-resistant tuberculosis (DRTB). Most of our patients come from Mumbai - a city of 22 million people, 43,464 of whom have TB, and 10 per cent whom are infected with drug-resistant strains of the disease. We also offer screening, diagnosis and specialised care for TB, HIV and hepatitis C in four clinics in the north-eastern state of Manipur. In addition, we provide care for people with advanced HIV in Bihar, one of the most populous states in India.

In the capital, Delhi, we provide medical and psychological care to survivors of domestic and sexual violence, and raise awareness about the importance of seeking timely medical and psychological care. We work with community-based organisations, police, government protection agencies and the health ministry to highlight the clinic’s services and create an efficient referral system. We also engage the community in discussions on domestic violence, sexual assault and child abuse.

Since 2001 we have been offering counselling in Jammu and Kashmir, where years of conflict have taken a toll on people’s mental health. Our work includes raising awareness of the support available, reducing the stigma associated with mental health, and emphasising the importance of seeking assistance.

In remote villages in Chhattisgargh, our teams conduct mobile clinics to take primary healthcare to areas where it is extremely difficult for people to access medical care. Our teams provide free treatment for malaria, respiratory infections, pneumonia and skin diseases among others.

Our activities in 2023 in India

Data and information from the International Activity Report 2023.

797

797

16.4 M€

16.4M

1999

1999

20,800

20,8

6,440

6,44

830

83

640

64

Explaining kala azar-HIV co-infection

Have you heard of kala azar?

Kala azar is a neglected but potentially fatal tropical disease. India accounts for 30 per cent of cases worldwide.

This short animation explains what kala azar is, how it relates to HIV, and what we are doing in response.

Since 80 per cent of India's kala azar cases are reported in Bihar, we set up a programme there in 2007.

People living with HIV are particularly vulnerable to kala azar, so since 2016 we have been focusing on treating patients co-infected with the two diseases, in partnership with the Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences (RMRIMS) in Patna, Bihar.

- Try a different country, year, format, or topic.

- Clear one or more filters

Contact us

5th Floor, Okhla NSIC Metro Station Building

New Delhi – 110020

India