“We had no food, no work and ended up with no home; my house was totally destroyed by the rain. That’s when I had to leave with my five-year-old and six-month-old children. I had to leave my nine-year-old son behind as I couldn’t afford the bus tickets for the four of us.”

Amel is from Gok Mashar in South Sudan and now lives in Kario Camp, in Sudan’s East Darfur. “I came here hoping that the situation would be better, but I’ve been living with my children in this reception tent with all the newcomers for a month now, still without a proper shelter.”

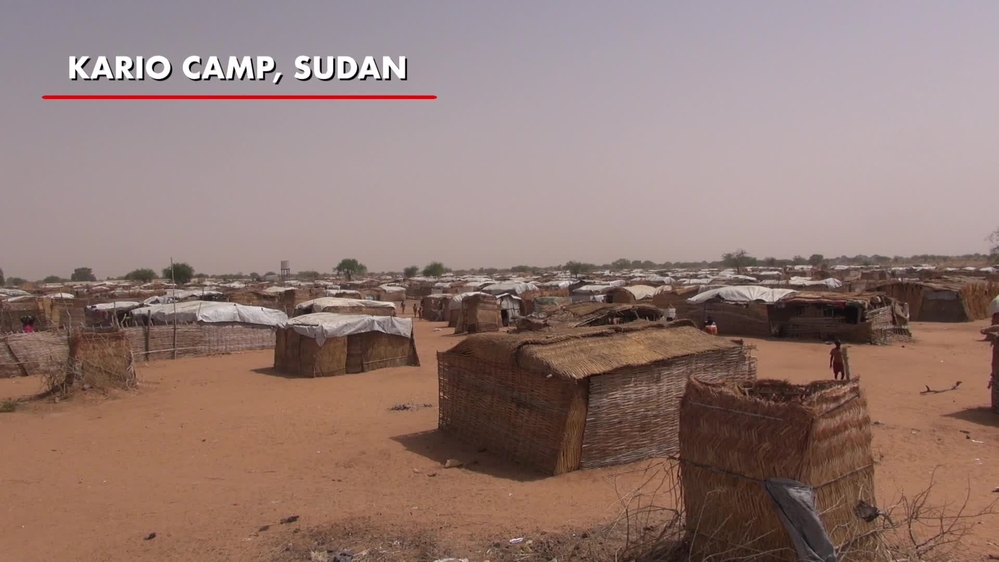

Kario camp reception centre is the first stop for South Sudanese newcomers waiting to be accommodated in Kario Camp. The camp registration unit receives refugees every day, most of them from South Sudan.

The MSF mobile team goes there twice a week to assess the health of the new arrivals. Vaccinations, malnutrition screening and referrals to the MSF facility in Kario are provided as necessary.

South Sudanese drifting back to Sudan

The violence and conflict in South Sudan have displaced millions, with roughly one third of the population having fled their homes. In East Darfur, many had left Sudan for South Sudan after the country’s independence in 2011, but they are now forced to return as a result of ongoing conflict.

There are more than 750,000 South Sudanese refugees currently in Sudan, according to the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR. Around 100,000 of them are in East Darfur, where MSF set up a hospital in July 2017, in Kario camp. The camp is the biggest refugee settlement in East Darfur, and today hosts around 20,000 refugees.

Vanessa Rossi, MSF field coordinator in East Darfur, describes the situation of the refugees in Kario camp: “Most of them don’t have a regular income; sometimes they work in the farms with the locals, but it’s seasonal work of course.”

“They are living in shelters made of local materials like wood and grass,” Vanessa explains. “Usually, big families of 5 to 10 people live in one small shelter in a very crowded space. The camp is full right now. People share the latrines outside their houses, which are filthy and muddy. The rainy season is approaching, and it’s going to be very long and difficult. Both in the camp and outside there will be many swamps and pools of stagnant water.”

Inside East Darfur's biggest refugee settlement

Worrying living conditions in Kario camp

People don’t have enough food. This is particularly impacting children, and pregnant and lactating mothers. If it continues, there is a high probability that the number of severe malnutrition cases will increase, particularly at the start of the lean season, between May and October.*

“Because of the heat and dust, we have many cases of upper respiratory tract infections, especially among children under five, in addition to pneumonia, dehydration, and some cases of malaria,” says MSF doctor Mohamed Zakria, describing the health situation in the camp.

“We also treat many cases of neonatal sepsis, a bacterial blood infection found in newborn babies, and puerperal sepsis, which is a genital infection that happens during labour or after. This happens because many deliveries occur at home without the proper hygienic conditions. We need to work more on health education in the camp and in the local community.”

The positive impact of the MSF project in Kario

When asked about MSF’s services in Kario camp, Ibrahim Korina, a Sudanese community leader in the Kario administrative unit, and one of the representatives of the community, said: “MSF’s health services are available and accessible to both refugees and locals in Kario. MSF’s presence in this region is essential for the prevention of, and the response to, the health needs of the population.”

MSF started its intervention in Kario in July 2017, during an outbreak of acute watery diarrhoea (AWD). MSF opened and ran AWD treatment centres with 20 beds, until the number of cases declined. Meanwhile, MSF upgraded Kario health centre into a hospital, providing free primary and secondary healthcare services, including maternity, nutrition and vaccination programmes for almost 40,000 people living in the area.

The staff in the health facility conduct between 200 and 300 outpatient consultations a day, for both refugees and members of the host community. The inpatient department has 20 beds and emergency cases are referred to Ed-Daein city hospital.

Dar Alnaeem, 20 years old, lives in Kario village. “In the past, we used to deliver babies at home with the assistance of a traditional midwife from our community, because there was no health centre available in the area,” she says. “When I knew about the opening of a maternity unit in the MSF centre, I decided to deliver here. It’s safer. After the delivery I was under observation with my baby for 24 hours. That’s how we discovered that he needs to be kept in the centre for follow-up.”

Since the AWD outbreak in 2017, prevention is one of MSF’s main concerns. “At least when we are present here, we can detect any possible outbreak and quickly apply the necessary measures to prevent further transmissions and possible outbreaks,” says Vanessa.

In December, MSF vaccinated 19,000 children against measles during a one-week immunisation campaign. On a daily basis, a team of 25 community workers walks around the camp and provides health promotion messages.

What next?

MSF’s Kario hospital is improving and expanding its health services to meet the needs of the increasing number of patients.

But despite the improved access to healthcare, living conditions for people in the camp remain dire. There are some concerns about the extent to which basic needs like food, latrines, water, sanitation, and suitable shelters are being met.

Especially in the reception centre, the dehumanising living conditions are also impacting on people’s mental health. Humanitarian organisations present need to improve the quality of their services, and ensure proper monitoring mechanisms are in place to evaluate the activities and their impact. Currently, the aid delivered in Kario is far below humanitarian standards.