What is the burden of malaria in Africa?

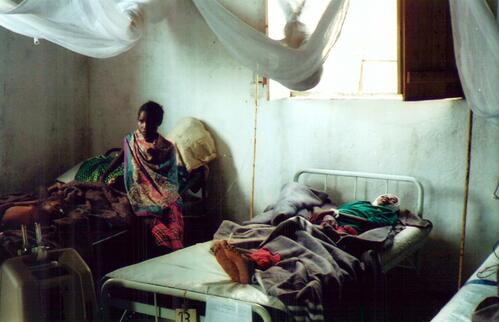

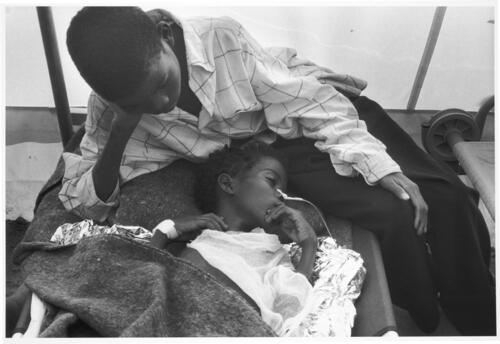

Malaria kills between 1 and 2 million people every year, the majority in Africa. It’s the first cause of death for children under five years of age – the disease kills one African child every thirty seconds.

Sickness and death from malaria account for 30-50% of hospital admissions and a yearly loss of US$12 billion on the African continent.

Is it getting better or worse?

The number of malaria cases were four times higher in 1990s than they were in the 1970s; and death rates in African hospitals have risen two- to three-fold. Since 1990, all-cause mortality for children has dropped in Africa, but malaria-specific mortality has been on the rise.

Between October 2000 and March 2001, a severe malaria epidemic in Burundi caused around 3 million cases in a population of 6.5 million people. The epidemic caused 13,000 deaths in just three provinces in the country.

Malaria is roaring back in Africa for several reasons, including migration (people with no immunity against malaria moving to malaria-endemic zones), weakened public health systems, changing demographics and land use. Resistance to antimalarial drugs is also responsible: continued use of ineffective drugs leads to increased cases of treatment failure, and treatment failure leads to rising rates of mortality, particularly among children.

How much of a problem is drug resistance?

Most African countries have high rates of resistance to classical antimalarial drugs such as chloroquine and sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP or Fansidar‚). For example, in 1999 Tanzania had chloroquine resistance rates from 28-97%, Kenya 66-87% and Uganda 10-80%. Today, in many African countries, resistance to chloroquine and SP is so high that both drugs are virtually useless.

Do better drugs exist?

Experts agree that the best current treatment is a combination of drugs that includes artemisinin derivatives, extracts of the Chinese plant Artemisia annua. Artemisinin derivatives are fast-acting, potent drugs that bring down the number of parasites in the blood faster than any other antimalarial drug. They also have few side-effects, and so far no resistance has been reported.

Artemisinin derivatives should always be used in combination with other effective antimalarial drugs (artemisinin-based combination treatment or ACT for short). Using a drug combination shortens the treatment course and makes treatment more effective, as each drug attacks different biochemical targets of the parasite. It also helps prevent resistance, as there is less chance of a parasite being simultaneously resistant to both drugs.

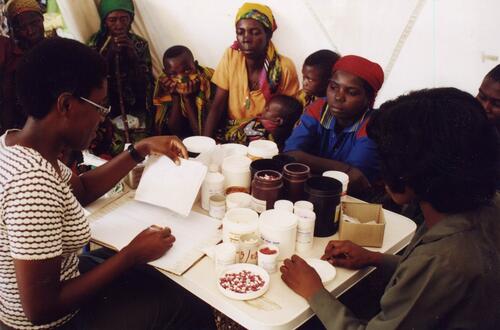

On the advice of international experts, WHO recommends African countries where resistance to old antimalarials has reached critical levels to replace single drugs with drug combinations, in particular artemisinin-based combination treatment (ACT). However, recommendations issued at headquarter level are not being translated into technical support at country level.

Why are African countries still using old ineffective drugs?

Several African governments have decided to change treatment protocols. KwaZulu Natal province in South Africa has successfully changed to ACT, and Burundi, Zambia and Zanzibar are preparing to implement ACT.

But many other countries have switched to another monotherapy (moving from one single drug to another, usually from chloroquine to SP) or to a combination of drugs that does not include artemisinin. The primary reason is lack of funds: ACTs are more expensive than old antimalarials, and many African countries can’t afford them.

How expensive are ACTs?

The cost of ACT is currently around US$1.50 (lowest quotes to humanitarian and government organizations for the combination artesunate amodiaquine). In contrast, the cost of treating an adult with chloroquine or SP is just US$0.10.

As orders for the drug increase, the price of ACT will drop over time. Based on current price trends, MSF estimates that the price of the artesunate-amodiaquine combination will be down to US$0.50-0.80 within 2 years. Costs must be subsidised by national governments with the help of international donors.

How much would switching to ACTs cost Africa?

Provision of ACT for all African countries that need it today would cost about US$100-200 million a year at current drug prices. For five countries – Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda – MSF estimated that only US$19 million in total would be needed to switch to ACT instead of a sub-optimal interim protocol.

ACTs are more expensive, but money is currently being wasted on cheap drugs that no longer work.

Are the drugs readily available?

Initial efforts to supply the first countries that have switched to ACTs have been thwarted by lack of supply. However, scaling up has begun and is feasible. The technology needed to extract and process the raw material is not very sophisticated. Putting the combination drugs into blister packs of into a single pill isn’t a big challenge to drug developers and producers.

Once markets are established by pooling orders and securing financing, producers will respond to the challenge. WHO, donors and involved governments must work together to encourage ACT production. It will take political will and expressed commitment to generate a demand-driven cycle for quality ACT raw material and finished products.

What are the positions of donor agencies such as DFID and USAID?

DFID and USAID have both adopted "go-slow" attitudes towards implementation of ACTs, suggesting that current protocols be "left alone" whenever possible.

The go-slow camp has claimed, among other things, that ACTs have not been proven safe and effective in Africa. In fact, artemisinins have been studied more extensively than any other antimalarials, and it is estimated that about 2 million people have so far been treated with ACTs with little report of serious toxicity. ACTs have been in widespread use in Asia for more than ten years.

It is also claimed that it is better to use a less effective treatment that can be given in one dose than a three-day ACT regimen. Rather than use this as an alibi to continue giving less effective medicines, the international community should support endemic countries to improve compliance through training, health education and improved packaging of medicines.

Donors should invest their time and resources into supporting the WHO’s recommendations to implement ACT now. But so far, they have been conspicuously silent on this issue.

What needs to be done?

- MSF urges the WHO to push for implementation of its own recommendation to switch to ACT.

- Donors must stop wasting their money funding drugs that don’t work and help fund efforts of endemic countries that make the switch to ACT.

- Endemic countries need to back up their will to improve malaria control with increased budget.

- International agencies and donors must provide technical support to facilitate both treatment implementation and upgrade international and domestic drug suppliers.

- UNICEF, WHO procurement and the Global Fund must pool needs and make large orders to prime drug production and bring down prices.

- In the long term, more research and development is needed to ensure new drugs, new formulations and improved diagnostic tools continue to reach the patients who need them.